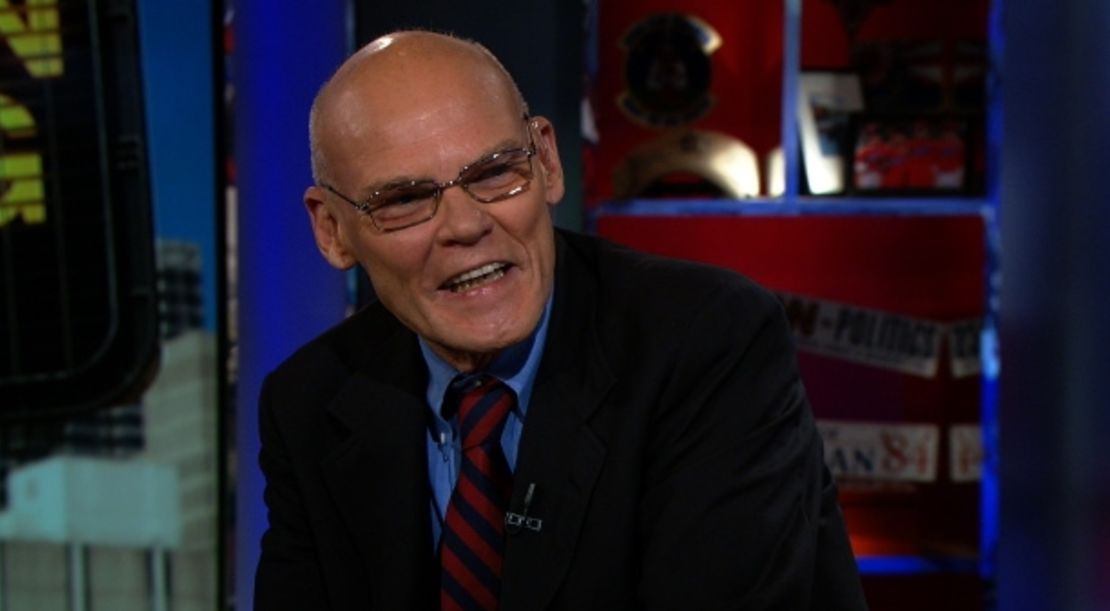

As President Donald Trump prepares to announce sweeping new tariffs on a broad swath of imports, Democratic strategist James Carville is sounding the alarm — not on the economics, but on the psychology behind the move.

Carville, the famously blunt former advisor to Bill Clinton, appeared on MSNBC’s "The Beat with Ari Melber" on Tuesday, delivering a scathing critique of Trump’s approach to trade and foreign policy.

“They’re just Trump going power mad,” Carville said. “And he figures, ‘I don’t have to get approval from Congress, I don’t need to bring it to the Cabinet, I can just do this.’”

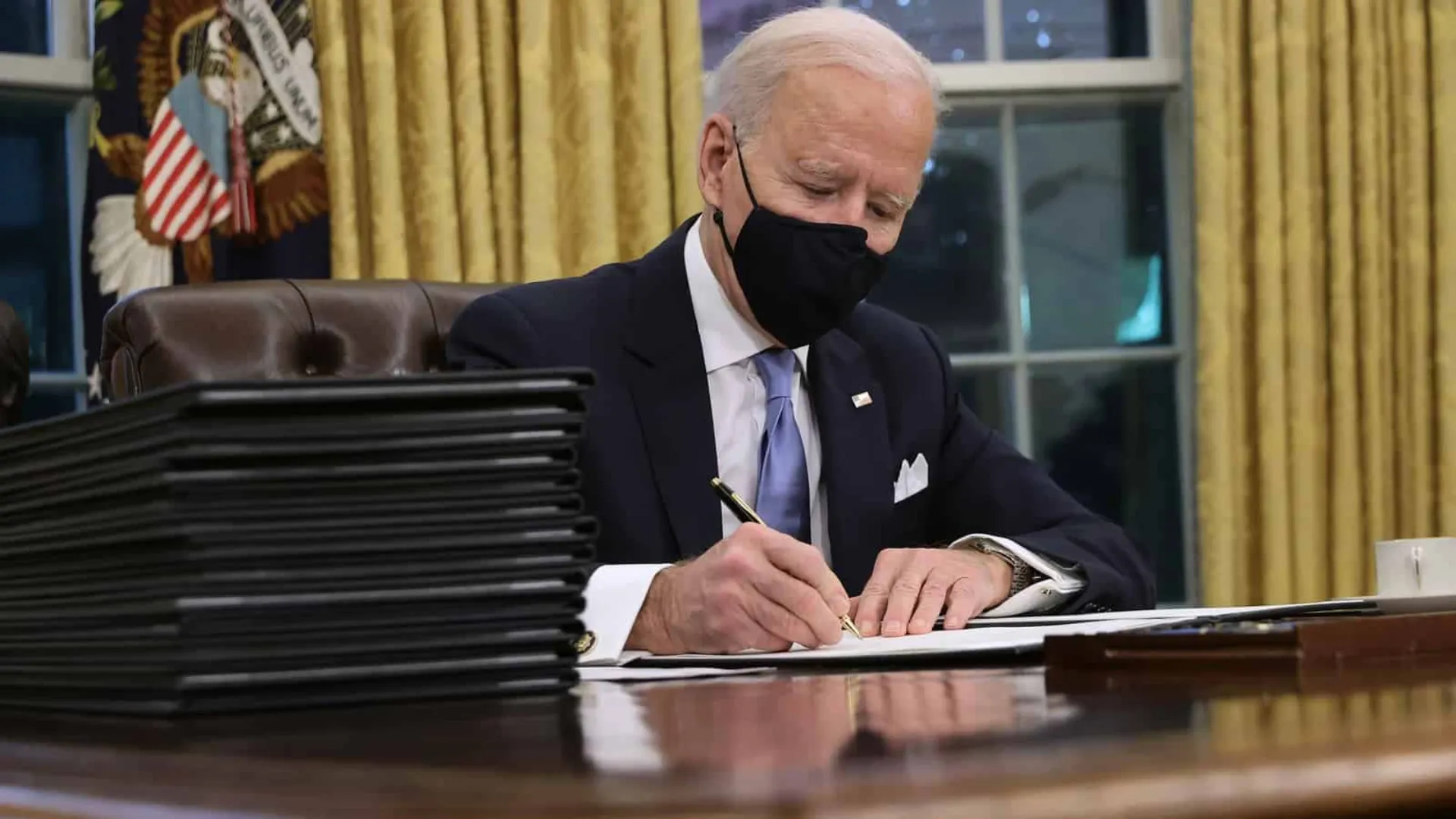

His warning came one day before Trump’s self-declared “Liberation Day,” when the president is expected to announce new reciprocal tariffs targeting dozens of countries.

While the administration has argued the tariffs are designed to protect American workers and level the playing field, critics like Carville see something far more personal at play. “It’s just his ego playing itself out in public,” Carville added. “And it’s going to hurt a ton of people that you can’t imagine.”

Carville’s critique taps into a long-running concern about tariffs: though they’re aimed at foreign producers, the costs are often passed directly to American consumers.

When host Ari Melber asked whether the tariffs amounted to “a tax on working people,” Carville didn’t hesitate. “Yes. It’s a tax. It’s a tax on American families. That’s what it is.”

Trump’s previous rounds of tariffs have shown similar effects. A 2020 study from the National Bureau of Economic Research found that U.S. consumers bore nearly the full cost of the tariffs Trump imposed during his first term — with particular impact on lower- and middle-income households.

The expected announcement on “Liberation Day” includes a 10% across-the-board tariff on all imports, as well as higher, country-specific tariffs for nations deemed to have unfair trade practices.

If Trump follows through on the proposal to target specific countries, it could reshape the global trade landscape. According to an analysis by CNBC, the countries most likely to be affected include: China, European Union (including Germany, Ireland, and Italy), Mexico, Vietnam, Japan, South Korea, Canada, India, Switzerland, Thailand, Taiwan

Combined, these countries represent a majority of America’s trade relationships, meaning the effects would be felt across almost every sector of the U.S. economy — from auto manufacturing and electronics to food imports and pharmaceuticals.

For Carville, the issue isn’t just that the tariffs will be economically harmful — it’s that Trump enjoys the chaos they cause. He painted a picture of Trump as a president who craves the spectacle of power more than the substance of governance.

“He loves having foreign people call and say, ‘Hey can you exempt Finnish steel from these tariffs?’” Carville said. “It’s all just a play.”

The suggestion is that Trump’s trade strategy is less about principle and more about leverage — a way to force foreign leaders to come to the table, acknowledge his authority, and offer concessions in exchange for exemptions.

Indeed, Trump has a history of announcing tariffs and later walking them back as a negotiating tactic. In 2018, he imposed steel and aluminum tariffs only to exempt several allies after political pressure. The pattern repeated in later disputes with China and Mexico.

Even before the full details of Trump’s latest tariff package have been revealed, industry leaders are sounding the alarm.

Executives from U.S. auto companies have asked for their sector to be spared, warning that the tariffs will raise production costs, reduce global competitiveness, and eventually lead to higher prices for American consumers.

Meanwhile, British Prime Minister Keir Starmer has publicly urged Trump to exempt the United Kingdom, citing the strong bilateral trade relationship and shared defense interests.

“We value our trade relationship with the United States,” Starmer said. “We hope that these proposed measures will not affect key UK industries.”

Beyond the economic and diplomatic concerns, Carville zeroed in on the constitutional implications of Trump’s move — especially his tendency to act unilaterally.

“The idea that he can just do something on his own, unilaterally, has great appeal to him,” Carville said. “He doesn’t want to ask Congress. He doesn’t want to build consensus. He wants to rule.”

Carville’s comments echoed broader critiques from legal scholars and former officials who worry that Trump’s approach to governance reflects executive overreach and a disregard for traditional checks and balances.

Trump has long argued that tariffs are a tool to restore balance to global trade and revive American manufacturing. During his first term, he launched trade wars with China, the EU, and others — moves that brought some concessions but also triggered retaliatory tariffs that hurt U.S. farmers, manufacturers, and exporters.

Farm subsidies increased dramatically under Trump to offset the pain. U.S. exports dropped in several sectors, especially agriculture and technology. Inflationary pressures grew as imported goods became more expensive.

Critics argue that the overall economic impact was disruptive, not productive. “Tariffs are taxes — and taxes that bypass Congress,” said economist Fiona Steele. “They’re a power move, not a growth policy.”

Why now? Many analysts believe Trump’s renewed push for tariffs is partly election-year positioning. With the 2024 race heating up, he’s returning to familiar themes: America First, trade nationalism, and economic patriotism.

Carville argues that underneath the messaging lies something more personal. “It’s not a strategy. It’s not a doctrine. It’s not a policy,” he said. “It’s just ego — raw and unfiltered — playing out in real time.”

With the new tariffs expected to be announced on “Liberation Day,” businesses, foreign governments, and American families are bracing for impact. Whether Trump’s strategy results in better trade deals — or another wave of economic turbulence — remains to be seen.

But as Carville put it, the motive isn’t hard to understand. “If it looks like ego, walks like ego, and tweets like ego — it probably is.”