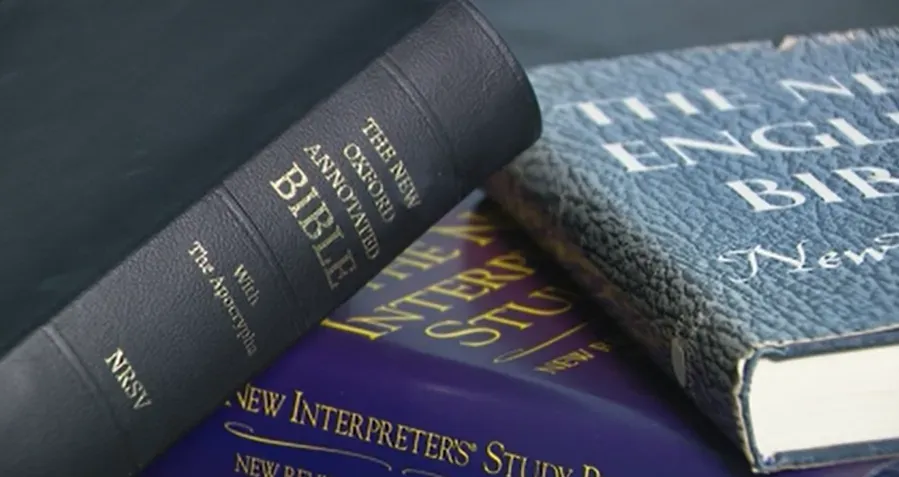

Oklahoma Superintendent of Public Instruction Ryan Walters has ignited a heated debate over his proposal to incorporate the Bible into public school education, sparking both praise and backlash.

The mandate, which Walters argues is essential for understanding American history and values, has drawn criticism from those concerned about the separation of church and state and inclusivity in education.

In a recent interview with CNN’s Pamela Brown, Walters defended his decision, stating that the Bible is not just a religious text but also a historical and cultural cornerstone. “If we’re going to talk about the foundation of our country, the Bible has to be part of that discussion,” Walters said.

He emphasized that his proposal does not mandate religious instruction but rather aims to use the Bible as a resource to teach history, literature, and civic values.

Brown challenged Walters on the implications of such a policy, questioning whether it would alienate students of other faiths or those who identify as non-religious. “How do you address concerns from parents and educators who say this blurs the line between church and state?” Brown asked.

Walters countered by asserting that teaching about the Bible in a historical and cultural context is not the same as promoting religious doctrine. “This isn’t about evangelizing; it’s about education,” he said.

The proposal has reignited broader debates about religion in public schools. Supporters of Walters’ mandate argue that the Bible’s influence on Western civilization, American founding documents, and moral philosophy makes it an invaluable educational tool.

They cite historical precedents, such as the use of the Bible in early American classrooms, as justification for its inclusion in modern curricula.

Critics, however, see the move as a dangerous precedent. Organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) have expressed concerns that introducing the Bible into public schools could violate constitutional protections.

“Public schools serve students from diverse religious backgrounds,” the ACLU said in a statement. “Introducing the Bible as a primary text risks alienating students and infringing on their First Amendment rights.”

Educators also voiced practical concerns about the policy. “If we include the Bible, are we also going to include religious texts from other traditions, like the Quran or the Bhagavad Gita, to ensure fairness?” asked one Oklahoma teacher, who preferred to remain anonymous.

Critics argue that a narrow focus on the Bible could marginalize students from non-Christian backgrounds and create an unequal educational environment.

The proposal has also drawn attention to the state’s broader educational priorities. Oklahoma currently ranks near the bottom nationally in academic performance and teacher pay.

Opponents of Walters’ plan argue that the state should focus on addressing these systemic issues rather than introducing potentially divisive policies.

The debate over the Bible in schools is far from resolved, as Walters remains steadfast in his position. “This is about restoring our values and teaching the truth about our history,” he said. Whether the proposal gains traction or faces legal challenges will likely shape discussions on religion and education nationwide.

For now, the clash over the Bible in Oklahoma’s classrooms serves as a microcosm of the larger cultural and constitutional battles playing out across the country.