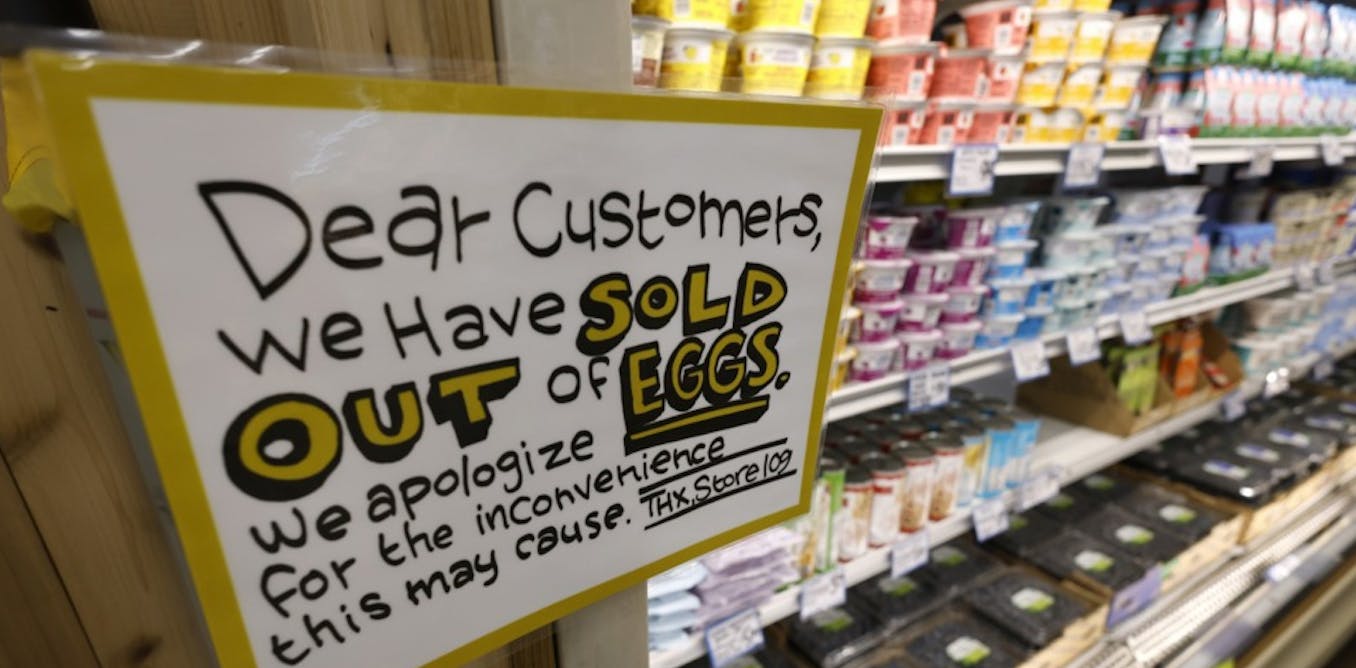

In a development that has caught the attention of both consumers and economists, egg prices in the United States soared to a record high in March, reaching an average of $6.23 per dozen, according to the latest report by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). This sharp rise has come despite recent statements from political leaders suggesting the economic outlook, particularly around food prices, was improving.

The increase marks a significant jump from February’s $5.90 per dozen and an even steeper rise from January’s average of $4.95. The price surge comes at a crucial time, as consumer demand typically rises ahead of the Easter holiday, which falls on April 20 this year.

While wholesale prices—the cost that retailers pay to suppliers—have reportedly dropped, the benefits of those reductions have not been passed on to everyday consumers. This disconnect between wholesale and retail pricing is raising concerns about supply chain dynamics, price transparency, and the broader state of food inflation in the United States.

In mid-March, White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt confidently told reporters, “Wholesale egg prices, they continue to fall. A dozen eggs are now $3.10 cheaper since January 24. That’s a 47 percent decrease overall. So I think the American people do have great reason to be optimistic about this economy.”

Former President Donald Trump also chimed in last month, claiming credit for previous improvements in food pricing. “When I took it over, eggs were through the roof, and now eggs are down,” he said at a recent campaign rally.

However, data from the BLS tells a different story for consumers at grocery store checkouts. Despite optimism from political figures, the average household is paying more than ever for a staple food item.

The egg index alone has surged over 60 percent in the past year, far outpacing general inflation trends and overshadowing modest improvements in other grocery categories.

Overall, the food index rose 0.4 percent in March. Particularly hard hit were categories like poultry, fish, eggs, and meats, which collectively rose by 1.3 percent over the same period.

The discrepancy between wholesale and consumer prices has ignited debate about the transparency and fairness of food pricing mechanisms in the U.S. economy.

The timing of the price surge is not accidental. With Easter on the horizon, demand for eggs typically climbs, driven by both culinary traditions and seasonal consumer behavior such as egg-decorating and baking. Retailers often anticipate this spike, but the extent of the price increase this year is unusual.

“Easter always brings higher egg demand,” said Laura Jenkins, a food economist based in Chicago. “But what we’re seeing now is a perfect storm of inflationary pressures, disrupted supply chains, and market uncertainty—amplifying what would normally be a modest seasonal uptick.”

Supply-side issues, including lingering effects from avian flu outbreaks, increased feed costs, and labor shortages in the agriculture sector, have all contributed to elevated production costs that ripple down to consumers.

For many American families, eggs are not just a holiday treat but a daily dietary staple. The sharp rise in prices has hit low- and middle-income households especially hard.

“I used to buy eggs every week for my kids' breakfasts,” said Maria Rodriguez, a mother of three in Texas. “But now, I can’t afford them every time. We’re cutting back.”

The story is similar across the country. Social media platforms have been flooded with complaints and memes about the skyrocketing cost of eggs, with some users joking that eggs are now "the new luxury item."

Retailers, for their part, claim their hands are tied. “We’re subject to the prices set by our suppliers,” said John Thomas, a regional manager for a major grocery chain. “Yes, wholesale prices have gone down, but we’re still dealing with the costs from previous months and ongoing volatility. We can’t slash prices overnight.”

The widening gap between political messaging and consumer experience is fueling skepticism and distrust.

“People don’t live in economic theory,” said Professor Dania Singh, an economist at UCLA. “They live in reality, and when they hear that prices are down but see a $6 carton of eggs in the store, it undermines trust in leadership—regardless of which party is in charge.”

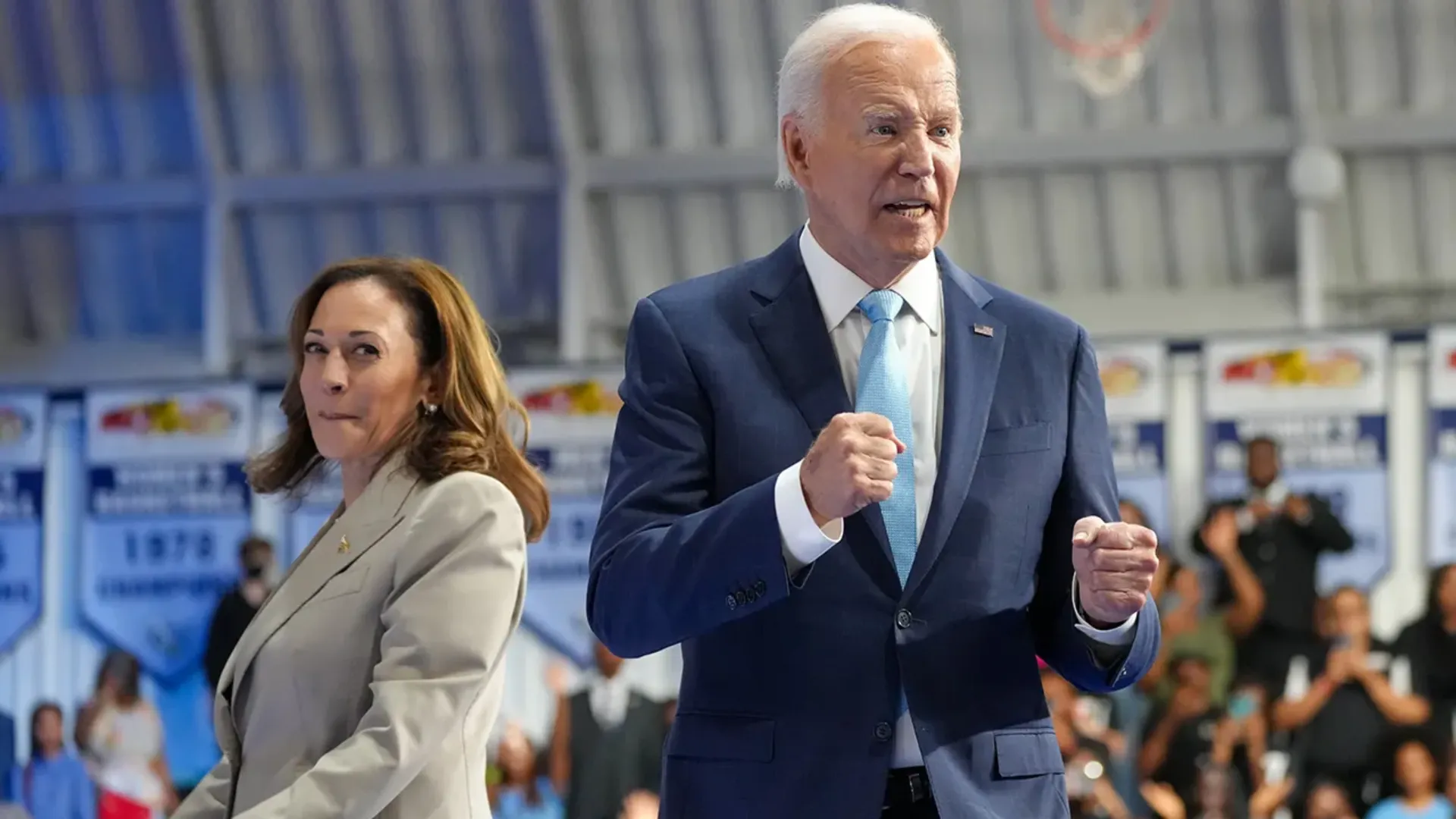

This gap presents a communication challenge for the Biden administration, which has been keen to highlight economic recovery and improvements in supply chains. With the 2024 presidential election still fresh in the public's mind, and political narratives continuing to dominate headlines, the economy remains a central issue.

Both major parties have made inflation a talking point, each blaming the other for what has become an extended period of elevated consumer prices across many categories, from groceries to gas.

Experts say the mismatch between wholesale and retail prices is a classic example of supply chain lag. Even when input costs begin to fall, retailers often have existing contracts and inventory that were purchased at higher prices. This results in a delay before consumers can see any real benefit.

“There’s a time delay between when wholesale prices shift and when shelf prices reflect those changes,” explained Dr. Henry Lawson, a professor of Agricultural Economics. “It can take several weeks or even months, depending on the supply agreements, regional distribution factors, and other market dynamics.”

Moreover, some critics suggest that retailers may be slow to reduce prices to preserve profit margins, especially after a tough financial year for many in the food retail sector.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Federal Trade Commission have both indicated they are monitoring the situation, with some lawmakers calling for more scrutiny into food pricing practices and corporate profits.

Meanwhile, consumers continue to feel the pressure. Budget-conscious families are seeking alternatives, with plant-based egg substitutes and bulk buying becoming increasingly common strategies to cope with the rising cost.

Economists suggest that if wholesale prices continue to trend downward, consumer prices should begin to reflect those changes by late April or early May. But with uncertainty still looming over key economic indicators, including oil prices, global supply chains, and labor markets, there is no guarantee of immediate relief.

The case of egg prices in early 2025 offers a striking example of how economic data, political messaging, and consumer experience can diverge in the real world. While government officials emphasize falling wholesale prices and express confidence in economic recovery, the average American is still shelling out record amounts for basic groceries.

Until consumer prices begin to reflect the reported drops in wholesale costs, frustration is likely to grow. For now, eggs remain a symbol—not just of Easter tradition, but of a larger story about inflation, trust, and the uneven pace of recovery.