Senator Chuck Grassley issued a sharp critique of congressional decisions dating back decades, arguing that the legislative branch has granted the executive far too much control over U.S. trade policy.

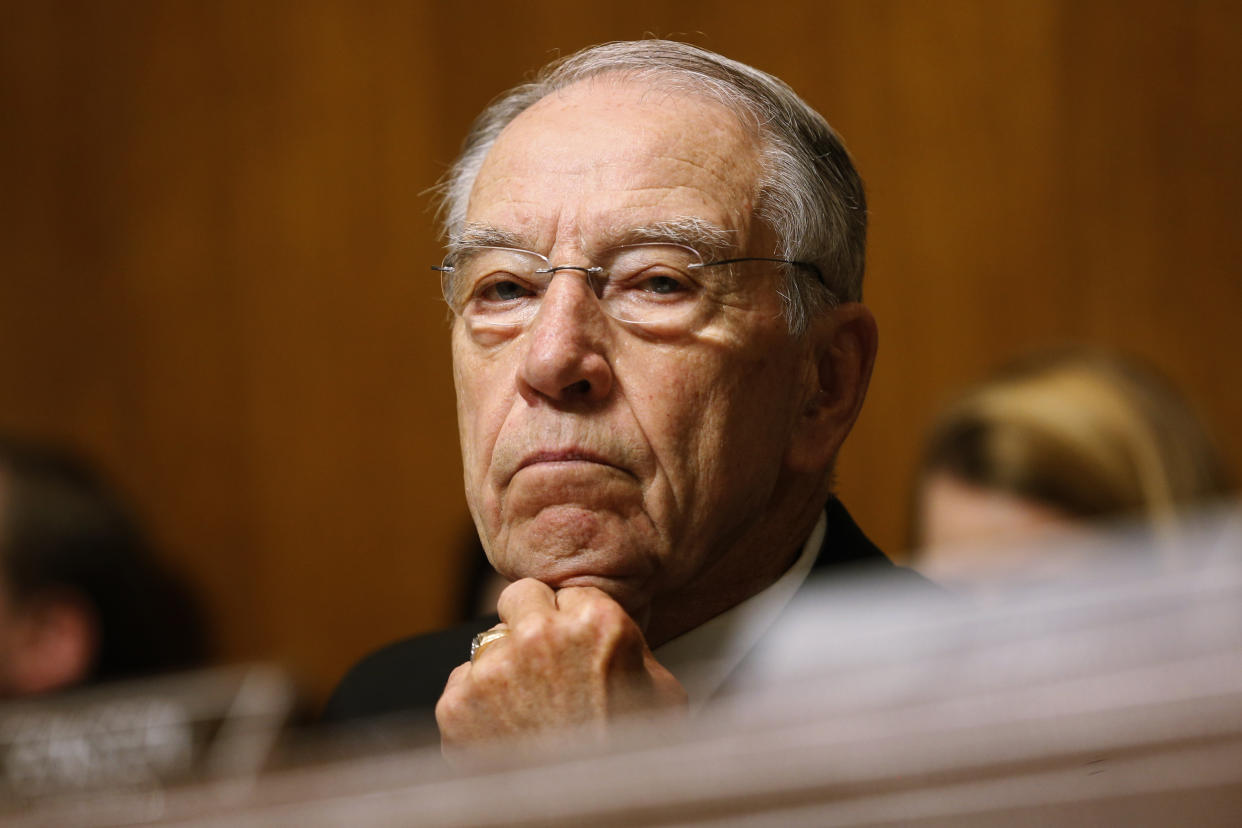

During a Senate Finance Committee hearing on Tuesday, Grassley voiced growing concerns about the president’s broad authority to unilaterally impose tariffs, calling for a reassessment of trade law and a rebalancing of power between Congress and the White House.

“I believe that Congress delegated too much authority to the president in the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 and Trade Act of 1974,” Grassley said. “It’s time we look at how much we’ve handed over to the president.”

The Iowa Republican’s remarks are part of a growing bipartisan effort to claw back legislative control over a domain that was once firmly rooted in congressional oversight.

Though he has been a longtime advocate of free and fair trade, Grassley has become increasingly vocal about what he sees as executive overreach in recent years—especially as past presidents, including Donald Trump, used tariffs as a key negotiating tool on the world stage.

“I’ve made very clear throughout my public service that I’m a free and fair trader,” he said. “But free and fair also means accountable—and we, in Congress, have to hold the reins.”

Still, Grassley struck a nuanced tone. He made clear that his critique wasn’t aimed at President Trump’s goals themselves, but rather the unchecked means being used to pursue them.

“I support President Trump’s agenda to lower tariffs and non-tariff barriers other countries impose on American goods,” he noted. “I also support his push to get a better deal from China and other countries for our farmers and manufacturers. But support for a mission doesn’t mean endorsing a blank check.”

Grassley’s comments came as U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer appeared before the committee to testify on the administration’s ongoing trade agenda.

Since 2018, Trump’s administration had imposed a wide range of tariffs on steel, aluminum, and other imports, triggering retaliatory measures from countries including China, Canada, Mexico, and the European Union. The resulting trade battles have impacted American agriculture, manufacturing, and consumer prices.

Grassley pressed Greer for clarity on the administration’s endgame. “My question to you is: In the medium to the long term, do you plan to turn these tariffs into trade deals to reduce tariffs and non-tariff barriers?” he asked.

“I support that. On the other hand, if the purpose is to stall on negotiations in order to keep tariffs high for the sole purpose of feeding the U.S. Treasury, I oppose that.”

Greer offered assurances that the administration’s intent is strategic, not financial. “The president stated very clearly that he is happy to engage in negotiations immediately with countries that believe they can help us reduce our deficit and get rid of the non-tariff barriers,” he replied. “It’s going to be country by country.”

He continued, “There are going to be some countries where they’re not able to address their non-tariff barriers or their tariffs, or the deficit fully, and there will be others who I think will be able to do that. In those cases, the president will have the option of making a deal.”

Grassley wasn’t satisfied with ambiguity, pushing further: “So is this administration for trade reciprocity or for Treasury replenishment?”

Greer acknowledged that increased tariffs naturally bring more revenue. “There’s obviously a revenue effect that comes with imposing tariffs,” he said, “but the bigger picture here is about reshoring manufacturing, correcting our agricultural deficit, and ensuring that trade is reciprocal.”

Greer emphasized that the administration is working to level the playing field for American workers and industries. “We need to make sure that if countries are going to trade with us, it has to be on a fair basis—where our businesses and workers aren’t put at a disadvantage,” he said.

This hearing wasn’t just a policy review—it marked a turning point in a broader legislative push. Grassley, along with Senator Maria Cantwell, a Democrat from Washington state, has introduced a bipartisan bill that would rein in presidential authority over trade.

The legislation proposes that any future tariffs imposed for national security or economic reasons must receive congressional approval.

At least seven Republican senators have expressed support for the bill, signaling a growing discomfort within the GOP over how presidential trade authority has evolved. “We’re not trying to hamstring the president,” Cantwell said in a recent statement. “We’re trying to ensure Congress has a seat at the table.”

The roots of the issue go back to the mid-20th century, when Congress passed laws that shifted certain trade powers to the executive branch. The Trade Expansion Act of 1962 gave the president the ability to negotiate trade agreements and adjust tariffs in response to global developments.

The Trade Act of 1974 built on this, allowing for additional authority under Section 301, which Trump would later use extensively against China.

These provisions were designed for flexibility in a rapidly changing world, but many now argue they’ve created an imbalance. “Back then, it was about speed and diplomacy,” said Georgetown law professor Marisol Medina. “Today, it's more about control—and Congress is feeling left out of the process.”

The consequences have been felt across industries. Farmers in Iowa, Ohio, and other agricultural states have faced mounting pressure due to retaliatory tariffs on soybeans, corn, pork, and dairy. U.S. manufacturers, meanwhile, have seen rising costs for imported materials.

Small businesses often find themselves squeezed between global supply chain disruptions and price increases.

Grassley, who represents one of the most agriculture-dependent states in the country, made sure his constituents' concerns were heard. “I’ve been very vocal in my wait-and-see approach to these tariffs,” he said. “But we need to make sure the endgame is real trade reform, not just temporary protectionism.”

The legislative push to reclaim authority also reflects shifting dynamics within the Republican Party. Once the party of free markets and global trade, the GOP has in recent years embraced more populist, protectionist economic messaging.

Some members welcome the president’s hardball tactics, while others, like Grassley, want to ensure the party doesn’t abandon its constitutional foundations.

Still, not all lawmakers are on board with reining in presidential power. Some argue that flexibility is essential in global negotiations, especially when other countries act quickly and unpredictably.

“We don’t want to tie the president’s hands in a trade war,” said one Senate aide, speaking on background. “But we also can’t let policy drift without oversight.”

Internationally, U.S. allies are also watching closely. European leaders, Canadian officials, and Asian trade partners have expressed frustration at sudden tariff hikes, often imposed with little warning.

Some view these measures as undermining the global rules-based trading system and weakening long-standing alliances.

“The world’s economic players are trying to make sense of what American policy is going to look like in five years,” said Jean-Pierre Dubois, a French trade attaché. “Will it be executive-driven? Will it return to bipartisan Congressional frameworks? That uncertainty has consequences.”

The debate over trade authority isn't just about steel and soybeans—it’s about the future architecture of U.S. economic governance. Lawmakers are asking hard questions about whether the balance of power reflects today’s realities.

Some are calling for a new Trade Modernization Act that would update the legislative framework to reflect digital commerce, global supply chains, and evolving labor dynamics.

“If we were writing the rules today, they’d look very different from 1962 or 1974,” Grassley said. “The economy has changed, the world has changed—and we have to change with it.”

As the bill gains traction and discussions continue behind closed doors, one thing is clear: the push to reclaim Congressional authority over trade policy has begun in earnest. Whether the legislation passes or not, the political ground is shifting.

Grassley ended the hearing with a sharp but measured tone. “If these tariffs are used to push for a fairer trade environment, I support them,” he said. “But if they’re used simply to fill the Treasury’s coffers, that’s something I cannot support.”

The real question now isn’t just about what past Congresses signed away—but whether this Congress is ready to take that power back.