In a contentious and highly partisan move, the U.S. House of Representatives voted on Wednesday to overturn a Biden-era rule that would have limited overdraft fees to $5 per transaction, a regulation that the White House previously claimed could save American consumers billions annually.

The measure, which passed 217-211, now heads to President Donald Trump’s desk, where he is expected to sign it into law.

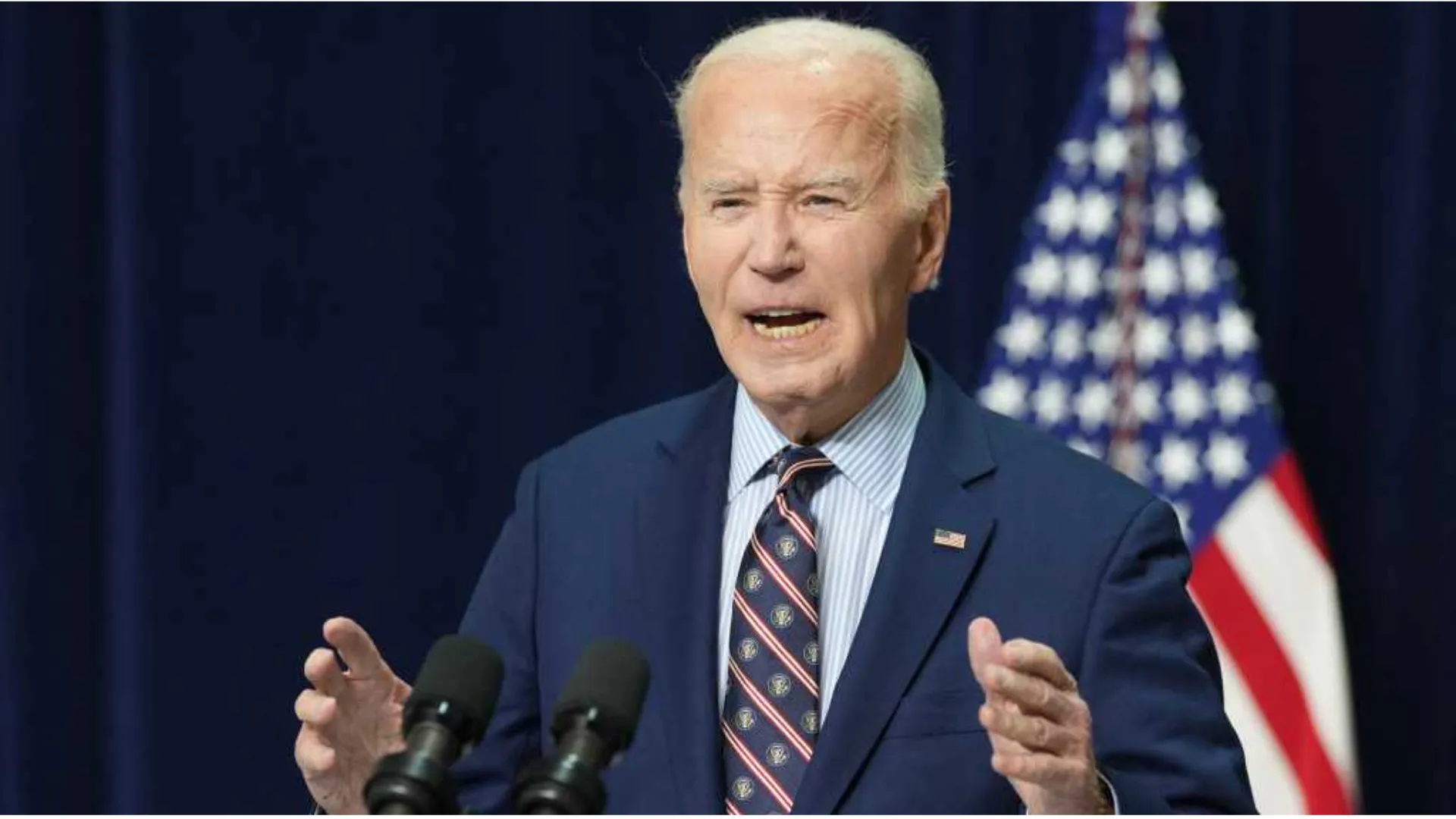

The vote comes after the Senate approved the resolution earlier this week, utilizing the Congressional Review Act to nullify the rule issued in the final months of President Joe Biden’s administration.

The regulation was scheduled to go into effect in October 2025, applying to major U.S. banks and credit unions with over $10 billion in assets.

The rule had been part of Biden's broader crackdown on so-called "junk fees" — charges added to basic financial products and services that disproportionately affect low-income and financially vulnerable Americans.

The regulation from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) was designed to bring overdraft fees in line with other consumer lending standards, arguing that the fees — which can range from $30 to $35 per transaction — are predatory and outdated.

Under the final rule, financial institutions would have had three options:

-

Charge a flat $5 fee per overdraft.

-

Charge a cost-based fee, determined by the actual cost of covering the overdraft.

-

Disclose the overdraft fee as a loan, with annual percentage rate (APR) calculations and full transparency, similar to credit cards or payday loans.

The CFPB estimated that this reform would save American consumers $5 billion annually, translating to about $225 per year per household that frequently incurs such fees.

“These fees are not about cost recovery,” the CFPB stated in its explanation of the rule. “They are about revenue extraction.”

Despite the projected consumer savings, Republicans pushed hard to overturn the rule, arguing that it would limit credit access, especially for those who rely on short-term overdraft protection in emergencies.

“This regulation would force banks to eliminate overdraft protection altogether,” said Rep. French Hill (R-Ark.), chair of the House Financial Services Committee. “Competition and innovation, not government-mandated price caps, remain the best way to ensure consumers have access to affordable financial products and services.”

Hill and other GOP leaders also warned that the rule would drive consumers to riskier, unregulated lenders, such as payday loan companies, pawnshops, or online lending platforms, which often charge exorbitant interest rates with minimal oversight.

In statements leading up to the vote, the American Bankers Association (ABA) echoed this concern. “Without access to overdraft protection, many Americans would be driven to less regulated and higher-risk non-bank lenders to cover unexpected or emergency expenses,” said Rob Nichols, ABA president and CEO.

Democrats, however, saw the repeal of the rule as a betrayal of working-class Americans. They argued that banks have become overly reliant on fees to generate revenue, often at the expense of those who can least afford it.

“Americans are fed up with these junk fees,” said Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Calif.), the top Democrat on the Financial Services panel. “Overdraft fees are not just inconvenient — they are exploitative. They punish people for being poor.”

Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.) was more direct, calling the repeal “shamefully targeting the American people.”

“These fees disproportionately impact people living paycheck to paycheck. A $3 coffee can end up costing someone over $30. That’s not banking — that’s extortion,” she said during debate on the House floor.

Overdraft fees have existed for decades, initially introduced as a way to ensure paper checks could be processed without bouncing — a convenience for both banks and customers. But since the early 2000s, these fees have evolved into a major revenue stream for banks.

Today, large financial institutions earn an estimated $8 billion annually from overdraft fees alone, according to public filings and CFPB data.

A majority of these fees — around 70%, according to the CFPB — are levied against consumers with average account balances between $237 and $439. Critics argue that this effectively penalizes the working poor for financial instability.

“This rule was about closing a loophole from a bygone era,” said Chuck Bell, advocacy program director at Consumer Reports. “Overdraft protection has transformed from an occasional courtesy into a core business model, and that needs to change.”

Republicans used the Congressional Review Act (CRA) to push through the repeal. This 1996 law allows Congress to reverse recent federal regulations with a simple majority vote in both chambers — as long as the rule was finalized within the previous 60 legislative days.

Under the CRA, once both the House and Senate vote to overturn a rule, the only step remaining is a presidential signature. If signed, the rule not only gets struck down, but a similar regulation cannot be reintroduced unless explicitly authorized by Congress.

The Senate passed its version of the resolution earlier this week by a narrow margin, with all Republicans and a handful of Democrats voting in favor.

President Donald Trump has not yet commented publicly on the House vote, but his economic advisors have strongly opposed the rule from the start, arguing that it was part of a broader “anti-business agenda” from the Biden administration.

Sources inside the White House have indicated that Trump is expected to sign the measure swiftly, making it one of the first major regulatory reversals of his second term.

Supporters of the repeal believe it will send a strong signal that the administration is focused on deregulation, market freedom, and pro-business policies.

For consumer protection advocates, however, the vote represents a major setback in the fight for fairer banking practices.

"This is a loss for consumers, plain and simple," said a spokesperson for the Center for Responsible Lending. "The argument that this helps consumers is disingenuous. It helps banks maintain an exploitative business model."

They warn that the repeal could embolden financial institutions to increase overdraft fees, especially with no federal cap in place. “This isn't about credit access,” the spokesperson added. “It’s about protecting billions in profit.”

With the rule’s repeal all but certain, banks will likely maintain — and potentially raise — existing overdraft fees. Consumers who frequently overdraft their accounts could continue to face charges of $30 to $35 per incident.

Critics of the repeal urge Americans to monitor their accounts carefully, avoid optional overdraft “coverage” plans, and consider switching to financial institutions that offer low-fee or no-fee overdraft alternatives.

Some credit unions and digital-only banks already cap overdraft charges at minimal amounts or waive them entirely as part of customer-friendly policies.

The vote is expected to become a campaign issue in the 2026 midterms, especially in swing districts where economic issues and financial fairness are top concerns.

Democrats plan to frame the repeal as yet another example of Republicans siding with big business over everyday Americans. Republicans, for their part, will likely present it as a defense of consumer choice and market flexibility.

With household debt at record highs and many Americans still struggling to manage expenses post-pandemic, financial regulations will likely remain a hot-button issue well into the next election cycle.

The repeal of the CFPB's overdraft rule marks a significant shift in the landscape of consumer banking policy — away from regulation and toward market-based solutions, at least in the eyes of the current administration and Congressional majority.

Whether that shift benefits the average consumer or simply preserves the profit margins of the nation's biggest banks remains to be seen. But one thing is certain: in an economy increasingly shaped by financial insecurity, even a $5 fee can make a difference — and, in Washington, so can a vote.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-2194451487-cea31a50c0b74e6ba635df1348f69890.jpg)